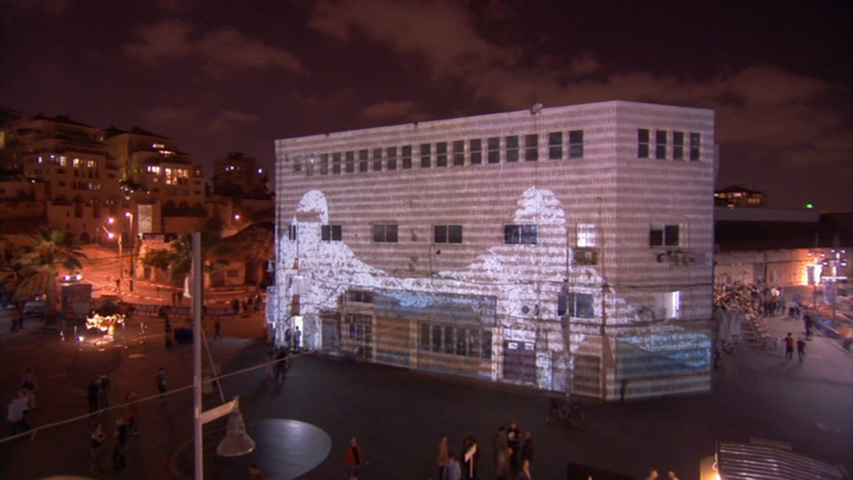

Still from the trailer for Gett (2014), directed by Ronit and Shlomi Elkabtez

Israeli films have made a global impact. Important recent contributions include Keren Yedaya’s Or (2004); Gidi Dar’s Ushpizin (2005); Joseph Cedar’s Footnote (2011); Meni Yaesh’s God’s Neighbors (2012); Rama Burshtein’s Fill the Void (2012); and Ronit and Shlomi Elkabetz’s trilogy, To Take a Wife (2004), Seven Days (2008), and Gett (2014). All of these have met with much acclaim from overseas audiences; Footnote was nominated for an Oscar; Or and God’s Neighbors both won major awards at Cannes; and the most recent of the Elkabetz’s films was nominated for a Golden Globe. Themes range from the ultra-secular to the ultra-Orthodox, from the harrowing to the comic, from the personal to the universal—sometimes all in a single work.

“Israeli films have made a global impact.”

Israel is of course at the center of one of the most fraught political situations in history; it is difficult even to mention the literary and cinematic arts without acknowledging that political tensions and clashes often provide pivotal subject matter—as with Grossman’s moving 2008 novel To the End of the Land, and Shani Boianjiu’s 2012 The People of Forever Are Not Afraid; and in film, Yaelle Kayam’s Graduation (2008), and Ari Folman’s devastating 2008 animated feature Waltz with Bashir (another Academy Award nominee).

But one recent documentary—made by U.S. filmmakers Karen Goodman and Kirk Simon (and produced by Lin Arison)—gave audiences hungry for good news about Israel something to think about. Their 2010 film Strangers No More focuses on a remarkable school in Tel Aviv called Bialik-Rogozin, where children from a wide variety of backgrounds, ethnicities, and faiths come together to learn. The film, which leaves viewers hopeful for a peaceful future for Israel and the region, in the hands of these wise and loving young people, received an Academy Award for Best Short Documentary.

The film Strangers No More, is available with the purchase of The Desert and the Cities Sing: Discovering Today’s Israel.

Trapped in a loveless marriage, Viviane Amsalem (Ronit Elkabetz) seeks a divorce from her devout and stubborn husband Elisha (Simon Abkarian) in Ronit and Shlomi Elkabetz’s Gett (2014).