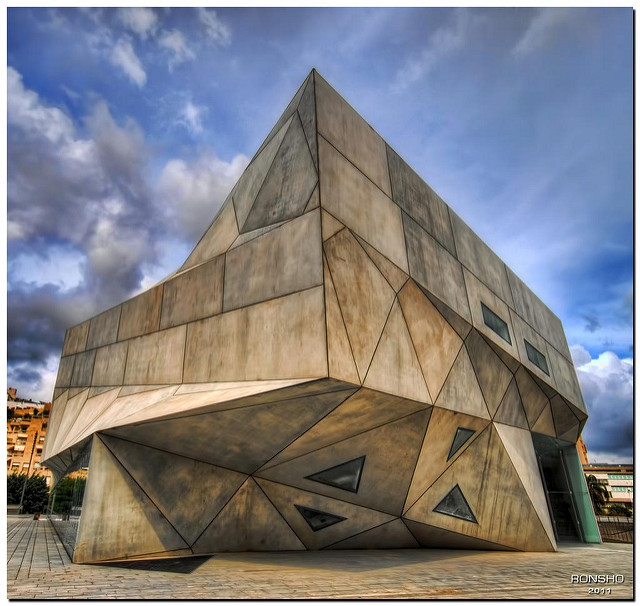

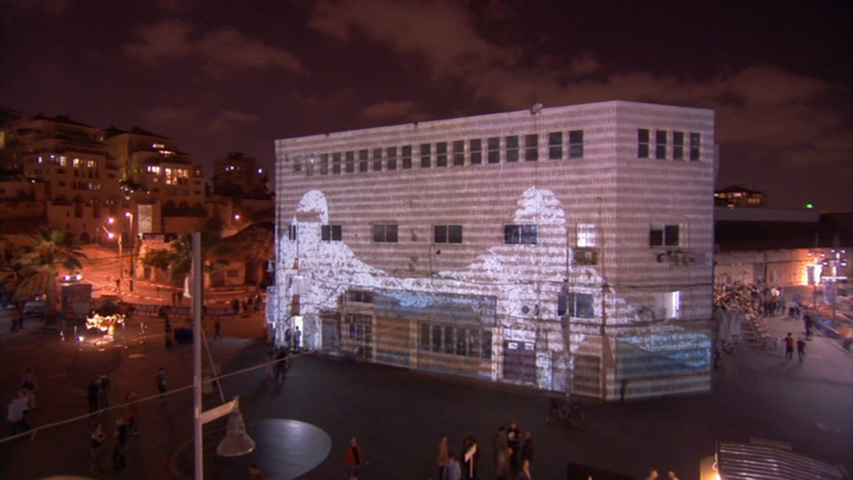

Debbie Kampel’s “Waterboys/Water Heart Face” for the Jerusalem Biennale. Photo: courtesy ISRAEL21C

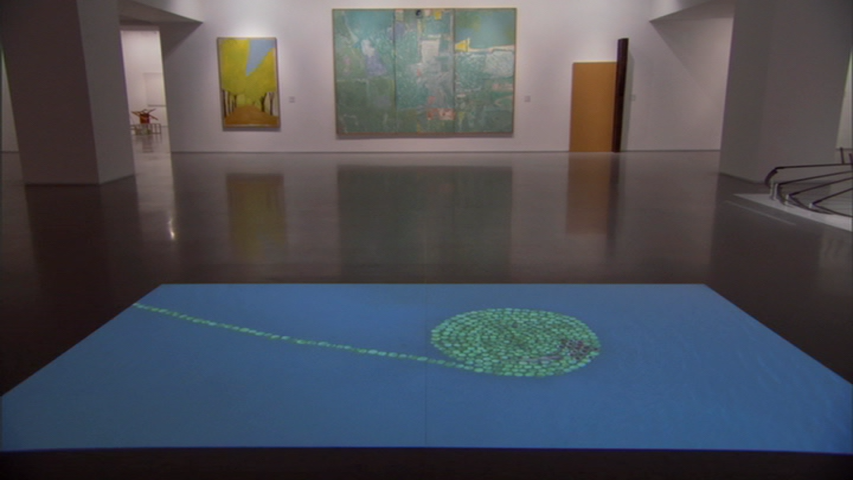

The Biennale runs from Oct. 1 to Nov. 16, 2017, encompassing 25 Jewish contemporary art exhibitions in several venues across the city.

If you’re in Jerusalem between October 1 and November 16, don’t miss the third Jerusalem Biennale, encompassing 17 group and eight solo exhibitions interpreting the theme “Watershed” through the lens of contemporary Jewish art.

The show includes photography, video, installation and performance art created by 200 artists hailing from diverse locales: New York, Los Angeles, Dallas, London, Paris, St. Petersburg, Budapest, Buenos Aires, New Delhi, Singapore and of course Israel.

“We’ve really become international,” Jerusalem Biennale founder and director Ram Ozeri says with pride. “This fulfils the vision we had from the beginning, to create a meeting point in Jerusalem for all those interested in the intersection between contemporary art and the Jewish world of content.”

The first Jerusalem Biennale in 2013 featured 60 artists, mostly Israelis. The biennale in 2015 attracted many artists from outside Israel but few from Europe. The third time was the charm, as Ozeri and his committee fielded 95 exhibition proposals from hundreds of artists across the world, not all of them Jewish.

The theme this year is “Watershed,” Kav Parashat Hamayim in Hebrew.

“In Hebrew, kav parashat hamayim is the drainage divide, the line at which raindrops split. If they fall west of the line they go into the Mediterranean and if they fall east of the line they fall on the Jordan Valley and Dead Sea. Jerusalem is that line,” Ozeri tells ISRAEL21c.

“In English, a ‘watershed moment’ changes the course of history. Jerusalem is a city where so many watershed events have changed the course of Jewish and world history.

“The theme allows us to ask metaphorical questions about identity, about the places in which we split into separate streams as human beings,” says Ozeri.

Venues include the Tower of David, Van Leer Research Institute, Austrian Hospice, Bible Lands Museum, Bezeq Building, Skirball Museum at Hebrew Union College, Museum of the Underground Prisoners and Achim Hasid.

Umbrella of Peace

A group of nine Indian artists built their biennale exhibition, “War and Peace,” around a shared watershed moment: Indian and Israeli independence from the British Mandate, which occurred in 1947 and 1948, respectively.

“When I read the history of Israel I found a lot of similarities between India and Israel. And I have been working on watershed themes for years, inspired by events in New Delhi,” curator and participant Hemavathy Guha tells ISRAEL21c.

She had no trouble finding artists eager to join in the group exhibition even though they are not Jewish.

One of the artists, Arpana Caur, “has given two of her paintings which depict the dual concepts of love and war with the use of guns and flowers and also touch upon the relevance of Buddha. She loved the magical Jerusalem, which she had visited earlier and recommended strongly that I should visit too,” says Guha.

Guha will bring her “Umbrella for Peace,” created from a sketch she’d done years ago.

“Flags of different countries have been printed on cloth and pasted on an umbrella, and all the countries have been connected with stitches and lines. I wish this earth would be devoid of war, terrorism and border conflicts and we could all live peacefully as it was intended to be,” she explains.

Vessels explored

Israeli artist Ofer Grunwald came to Ozeri’s attention because of his critically acclaimed exhibition in October 2016, “Disconnected Medium,” using bonsai (living tree sculptures) as a platform for contemporary artistic expression.

“My emerging artist status is based on the shockwaves of that exhibition,” says Grunwald, an Israeli native and resident of Jerusalem since 2009. He currently is “reimagining” the bonsai collection at the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens as part of a strategic partnership.

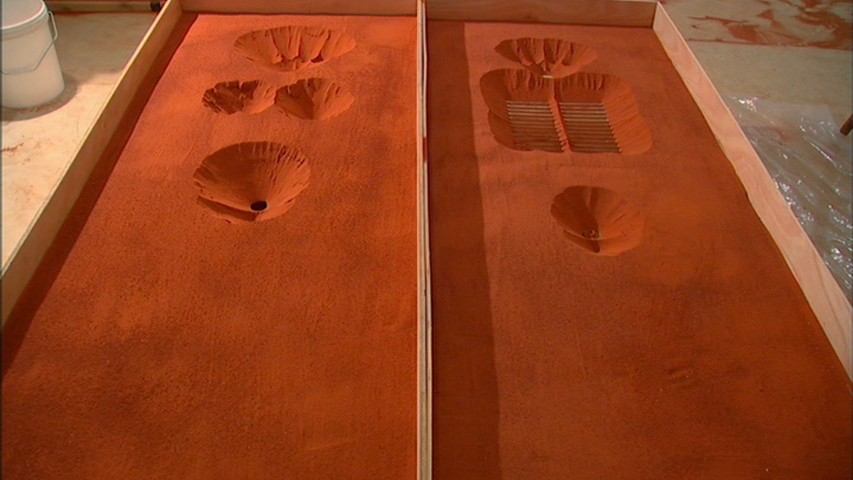

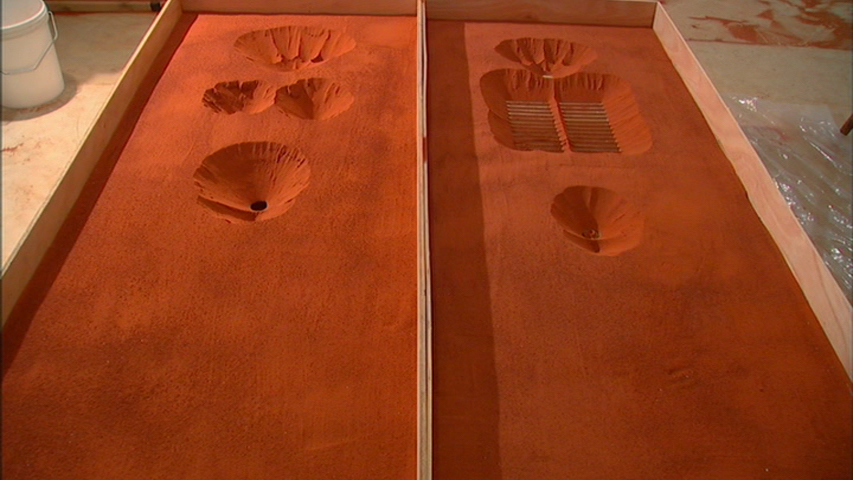

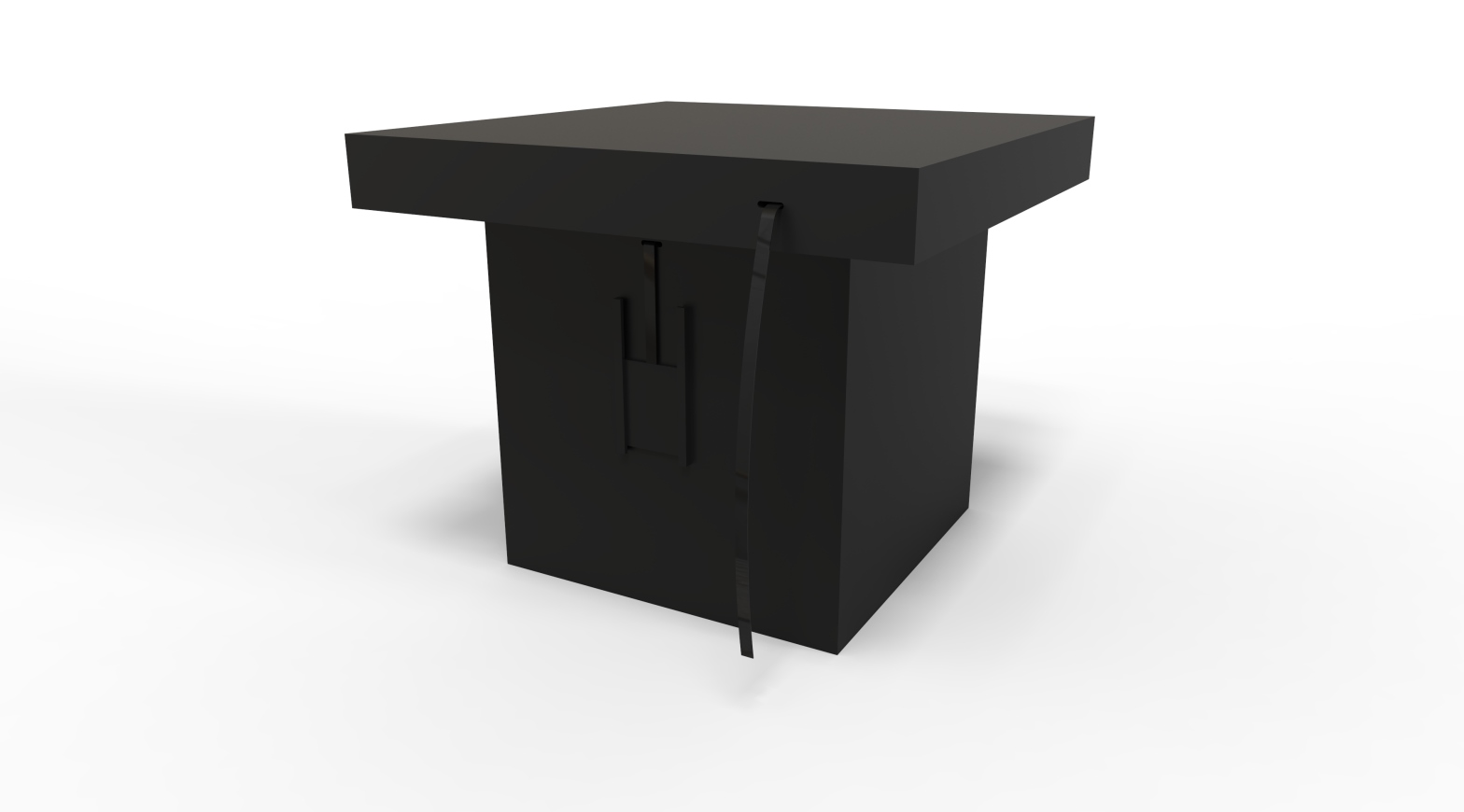

For the biennale, Grunwald created “Vessels,” a series of five installations that capture the tension inherent in waiting to see on which side of the divide the raindrops fall, or metaphorically the emotive sense of tension within the context of contemporary Judaism.

“The series tries to explore that by taking Jewish religious objects like tefillin and fetishizing their utilitarian attributes — for example, the tefillin’s leather straps have fetishistic overtones of restraint,” Grunwald says.

He made a tefillin-shaped cube with a sculpture inside, and peep holes operated by pulling the leather strap. “Opening one peep hole closes the other, and so the work creates a conflict between visitors to the exhibition, where one’s gaze negates the other,” Grunwald tells ISRAEL21c.

Private and group tours of the biennale are available in English. Information: tours@jerusalembiennale.org

For general information, click here.