Still from the YouTube video "Carrefour, the uniform that cares" by Saatchi & Saatchi IS

Jerusalem-based Argaman Technologies’ bio-inhibitive cotton is being made into facial masks, hotel linens, uniforms, active wear and much more.

The constantly intensifying battle against viruses and antibiotic-resistant “superbugs” isn’t only about finding stronger drugs against infection. The focus is moving to preventing infections in the first place.

That’s why large companies such as Carrefour and a Far East luxury hotel chain are looking at unique germ-vanquishing textiles invented by Jerusalem’s Argaman Technologies and manufactured inside its custom-built factory.

Carrefour Group, a French-based superstore chain with 12,000 retail stores in 30 countries, is testing Argaman’s CottonX — billed as the world’s first bio-inhibitive 100 percent cotton – in a line of uniforms dubbed “The Uniform that Cares.”

Textile engineer Jeff Gabbay, founder and CEO of Argaman and inventor of CottonX, led ISRAEL21c on an exclusive tour of the factory, where enhanced copper-oxide particles are ultrasonically and permanently blasted into cotton fibers using an environmentally friendly technique.

Argaman Technologies’ machinery was custom designed for cavitating cotton with active copper oxide. Photo: courtesy Israel21C

Ninety-nine percent of bacteria and viruses are killed within seconds of coming into contact with copper oxide, and bacteria cannot become resistant to copper oxide as they do to antibiotics, Gabbay explains.

Hospital-acquired infections cost US hospitals about $25 billion annually. A trial by the US Centers for Disease Control has recently been completed, checking the effectiveness CottonX sheets, pillowcases, and pajamas to reduce hospital-acquired infections. Results will be published soon.

CottonX is the first-ever bio-inhibitive 100% cotton. Photo courtesy of Argaman Technologies

Face masks for China

CopperX is being developed into reusable, comfortable face masks for the Greater China market, where airborne pollution is a major problem, says Edwin Keh, head of the Hong Kong Research Institute for Textiles and Apparel.

This government-run, nonprofit applied research and commercialization center was introduced to Argaman last year as the result of the industrial R&D memorandum of understanding signed by Israel and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China Hong in February 2014.

One of the largest garment manufacturers in the world, also based in Hong Kong, became a strategic investor in Argaman.

These masks kill, rather than filter, viruses and bacteria as they pass through. Photo courtesy of Argaman Technologies

Keh tells ISRAEL21c that in addition to the masks, his institute also is testing the applicability of the self-sterilizing, hypoallergenic CottonX material in airline cabin interiors and in hotels.

“Our intention is to license the Argaman technology and marry it with some manufacturing and processing technologies on this end to produce commercial-scale products – probably curtains, towels and bedding — to keep environments more hygienic.”

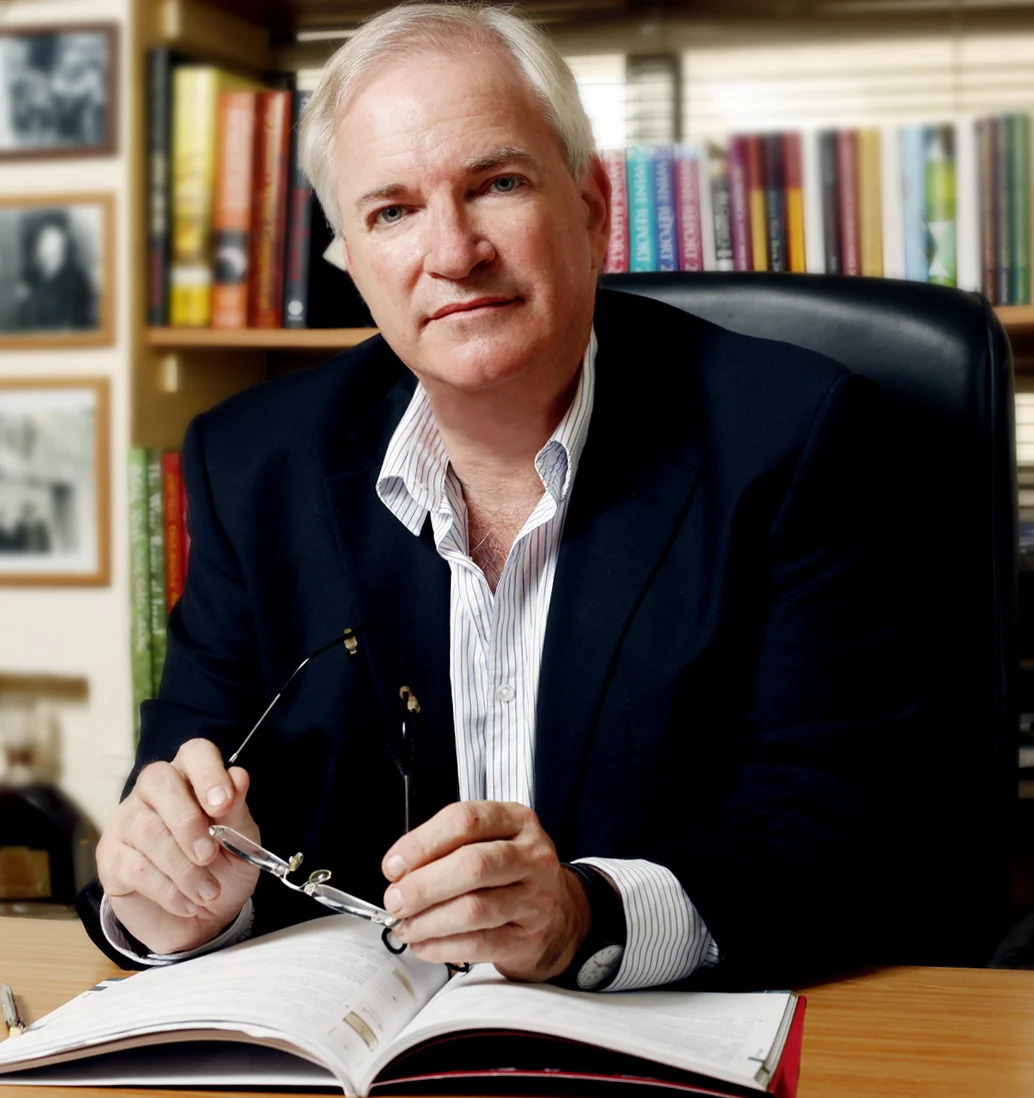

Edwin Keh, head of the Hong Kong Research Institute for Textiles and Apparel. Photo: courtesy

Keh says he hopes to pursue collaborations with additional Israeli companies offering advanced technologies for the textile industry, especially in water management, spinning, dyeing, weaving and cotton agriculture.

“We want to make a success story out of our collaboration with Argaman and we hope it will be the first of many,” says Keh.

Fire-resistant, wrinkle-fighting

Keh is also interested in some other properties of CottonX aside from germ control.

Embedding varying concentrations of copper dioxide also makes the fabric fire-resistant, electricity conductive (potentially useful for medical monitoring and military markets) and capable of banishing facial wrinkles and even cellulite.

“We know how much active ingredient we need in the fibers to be effective for different purposes, from banishing wrinkles to killing stubborn bacteria. By being able to control the active ingredient content we can assure completely consistent quality in everything we do,” says Gabbay.

CottonX healthcare socks for preventing athlete’s foot and diabetic foot ulcers will soon be launched. Cosmetic textiles — facial mask, pillowcase, gloves, socks and scarf, each premium packaged with an all-natural bio-inhibitive cream infused with accelerated copper oxide – are being developed jointly with a US company headed by a former L’Oréal and Revlon executive.

Argaman also is in discussions with a global fashion firm to create a new “lifestyle” brand of products.

The Argaman Technologies team in its Jerusalem factory. CEO Jeff Gabbay is fourth from right. Photo: courtesy

Still in the development stage at Argaman are garments that can deliver transdermal chemotherapy or other pharmaceutical treatments and an optic-fiber-embedded material that could deliver phototherapy to psoriasis patients or to jaundiced newborns.

Argaman is a member of a new five-year consortium established in the Israel Innovation Authority’s MAGNET program, which aims to unite technology and industrial companies with academic research institutes to develop technologies for producing “smart” fabrics.

“Not only are we built to take the concepts from academia — plus a lot of our own ideas — to the level that industry needs but we also have the ability in-house to supply all industrial members the understanding of the science, samples and industrial quantities of the new materials should the concepts go commercial,” Gabbay says.

For more information, click here.

Article courtesy of www.Israel21c.org