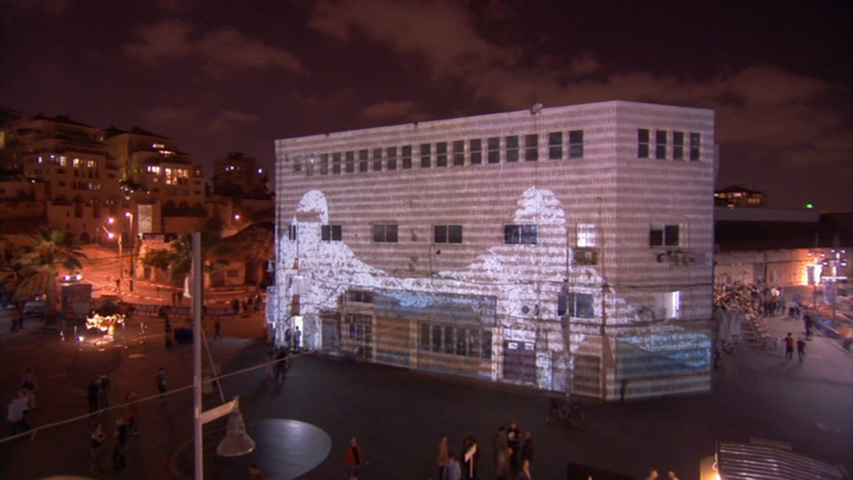

Expressive graffiti in Jaffa

The Jaffa seaport is one of the oldest harbors in the world; it has been in use, they say, since the Bronze Age. So today, just as they did nine thousand years ago, ships bring in cargo, and sun-baked fishermen pull in nets wriggling with mullet, grouper, and sea bream. The port is alive with crowds, shops, and restaurants—and naturally, it has its share of galleries.

“One of the oldest harbors in the world”

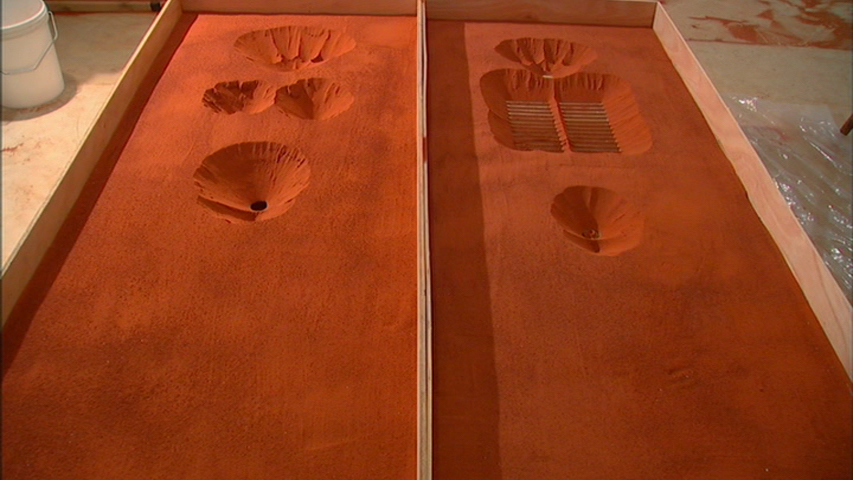

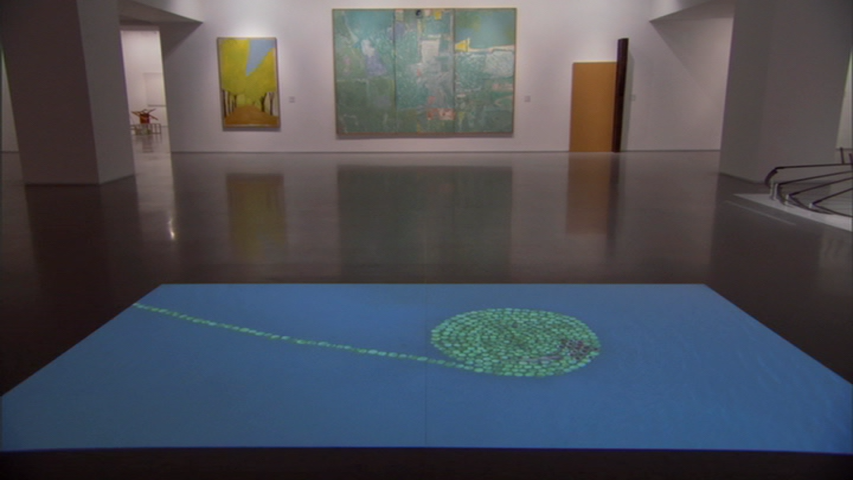

The artist-run Ilana Goor Museum, filled with a jungle of sculptures and objects, has been open to the public for many years, but there are newcomers to the neighborhood. Zadik—described by its director, Hana Coman, as “the people’s gallery of Jaffa”—is a long, pale-walled space hung with contemporary works; the gallery also hosts evenings of lectures and live music. Inga Gallery features conceptual artists from Israel and abroad, while Tempo Rubato presents everything from 2-D work to full-scale installations. As in Kiryat Hamelacha, many of the public walls in this quarter are covered with street art and graffiti: cartoon monsters, jaggedy boys and girls, fierce 2-D animals, and words in the Western, Hebrew, and Arabic alphabets. It is also home to the Jaffa Art Salon, a vast, cavelike gallery filled with works by a variety of artists from the area.